HOW POOR DO YOU HAVE TO BE TO BE BELOW THE POVERTY LINE?

The federal poverty level is an archaic definition for poverty that is the same whether you live in rural areas of Nebraska or urban areas such as NYC. The poverty level for a single person in 2020 was just $12,760; for a parent and one child it was $17,240; for a parent and two children, it was $21,720. You get the picture. Could you pay rent in NYC and food and transportation and childcare and medical on that?

The $15/hour minimum wage law in New York City is an important step towards helping low wage workers obtain fair pay for their work. But let me be clear: in our city, the “minimum” is way below the “livable’.” Too many people in the government—local, state and federal—conflate “minimum” with “livable” and pat themselves on the back for “lifting people out of poverty.” Not true.

When a family of three makes $30,000 a year instead of $20,420, are we really “lifting them out of poverty” as the Mayor so proudly states or is the poverty line too out-of-date? People are food insecure because they have to make horrible choices: Do I pay the light bill or buy fresh fruits and vegetables and milk and chicken? Do I pay for my medication or the train to go to work? Food insecurity is about poverty. And in NYC, whether you live in the Bronx or Queens, Staten Island or Brooklyn or Manhattan, $21,740 is not enough to live on for a mother and her two children.

This “lifting” people over an antiquated divider line may make a more fortunate class feel better about itself but it actually perpetuates the hierarchical thinking that certain people are lesser because they can’t pick themselves up by their bootstraps. Way back in 1965, President Lyndon Johnson, having instituted the Equal Opportunity Law as part of the war on poverty said “You do not take a person, who for years, has been hobbled by chains and liberate him, bring him up to the starting line of a race and then say "You are free to compete with all the others,’ and still believe that you have been completely fair.” Yet we all do take that person to the proverbial starting line and expect miracles.

If we clearly and unabashedly wanted to lift people out of poverty, we would confront inequality head on, and ensure that all people could afford the fundamental requirements of living: a decent place to live, schools with high standards, transportation that was affordable and convenient, childcare that was free, and healthy food that was accessible to all. In fact, the United States is almost last in the world in its care of its children.

So when we applaud ourselves for “lifting people out of poverty” we malign those who don’t magically rise up to a higher level, knowing full well that they cannot. “Minimum” has little meaning if it is insufficient for necessary costs for minimum living quality.

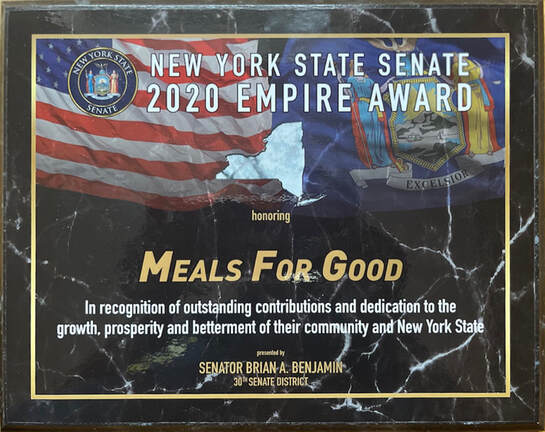

This is why Meals For Good was born: to add a little bit of help, and reduce some of the angst of food insecurity (at least) by supplying fresh, healthy food for people who can’t afford it in their own communities.

While we fight for a livable wage for all, one that includes decent housing, decent healthcare, decent education and decent food, Meals For Good is at least trying to help make “minimum” a little more livable.

The $15/hour minimum wage law in New York City is an important step towards helping low wage workers obtain fair pay for their work. But let me be clear: in our city, the “minimum” is way below the “livable’.” Too many people in the government—local, state and federal—conflate “minimum” with “livable” and pat themselves on the back for “lifting people out of poverty.” Not true.

When a family of three makes $30,000 a year instead of $20,420, are we really “lifting them out of poverty” as the Mayor so proudly states or is the poverty line too out-of-date? People are food insecure because they have to make horrible choices: Do I pay the light bill or buy fresh fruits and vegetables and milk and chicken? Do I pay for my medication or the train to go to work? Food insecurity is about poverty. And in NYC, whether you live in the Bronx or Queens, Staten Island or Brooklyn or Manhattan, $21,740 is not enough to live on for a mother and her two children.

This “lifting” people over an antiquated divider line may make a more fortunate class feel better about itself but it actually perpetuates the hierarchical thinking that certain people are lesser because they can’t pick themselves up by their bootstraps. Way back in 1965, President Lyndon Johnson, having instituted the Equal Opportunity Law as part of the war on poverty said “You do not take a person, who for years, has been hobbled by chains and liberate him, bring him up to the starting line of a race and then say "You are free to compete with all the others,’ and still believe that you have been completely fair.” Yet we all do take that person to the proverbial starting line and expect miracles.

If we clearly and unabashedly wanted to lift people out of poverty, we would confront inequality head on, and ensure that all people could afford the fundamental requirements of living: a decent place to live, schools with high standards, transportation that was affordable and convenient, childcare that was free, and healthy food that was accessible to all. In fact, the United States is almost last in the world in its care of its children.

So when we applaud ourselves for “lifting people out of poverty” we malign those who don’t magically rise up to a higher level, knowing full well that they cannot. “Minimum” has little meaning if it is insufficient for necessary costs for minimum living quality.

This is why Meals For Good was born: to add a little bit of help, and reduce some of the angst of food insecurity (at least) by supplying fresh, healthy food for people who can’t afford it in their own communities.

While we fight for a livable wage for all, one that includes decent housing, decent healthcare, decent education and decent food, Meals For Good is at least trying to help make “minimum” a little more livable.

LIVING WITH FOOD INSECURITY

Potatoes can teach us a lot about what it means be food insecure.

Let me explain: I always thought that pantries would order produce they cannot obtain through the Emergency Food Programs. I was surprised then, that so many of them ordered onions and potatoes first. Potatoes are inexpensive and can be ordered at approved government sites with canned and boxed foods. Plus City Harvest and the Food Bank often have potatoes to distribute for free. So I thought, why should they order potatoes from us?

Pantries do order lettuces, etc, but more often they order more durable produce such as carrots, cabbage, potatoes and onions. At first I was taken aback, and wondered whether I should push them to order more greens.

But this is what I discovered:

Food insecurity makes people want plenty, in fear of never having enough.

The picture below shows people waiting at 7 a.m. to get into a pantry that opened at 8 a.m. The line was three quarters down the block.

Let me explain: I always thought that pantries would order produce they cannot obtain through the Emergency Food Programs. I was surprised then, that so many of them ordered onions and potatoes first. Potatoes are inexpensive and can be ordered at approved government sites with canned and boxed foods. Plus City Harvest and the Food Bank often have potatoes to distribute for free. So I thought, why should they order potatoes from us?

Pantries do order lettuces, etc, but more often they order more durable produce such as carrots, cabbage, potatoes and onions. At first I was taken aback, and wondered whether I should push them to order more greens.

But this is what I discovered:

- These durable foods don’t go bad as quickly, and don’t have to be refrigerated, so storage is easier.

- Sometimes the durable foods from the food programs are badly bruised.

- Because these foods are inexpensive, pantries like to be more generous with how much they give out so they are always looking for more.

- Not everyone likes mushrooms, or arugula or lettuces that look different from what people are used to—and people who are food insecure cannot afford to taste test. They need foods they know their families will like, foods they know everyone will eat.

Food insecurity makes people want plenty, in fear of never having enough.

The picture below shows people waiting at 7 a.m. to get into a pantry that opened at 8 a.m. The line was three quarters down the block.

A DAY AT THE FOOD PANTRY

She took her bags of free food from the pantry four blocks away and hoped for something delicious and fresh. Let’s call her Ashley. She had waited in the cold for an hour until the doors opened and they got to her number in the line. The pantry was downstairs in the basement of the church. The basement stairs were slippery and steep from the recent icy rain, with a rickety railing only on one side. She had brought her shopping cart, hoping to get a few extras to lug back home. Sometimes the pantry had a table of ‘extras’ of food. She received three plastic bags because she had two children plus herself. Each bag had the same foods. Still, it was healthy food. And if was free, so if there were things her kids didn't like, she didn't have to feel she was wasting money if they refused to eat it. (She was diligent and tried to give her children new foods when she could). The people who gave out the food bags were nice.

Spaghetti sauce is counted as a vegetable. Is it, she wonders? Well her kids like it, so she hopes it’s a vegetable. She has gotten a lot of spaghetti sauce lately, and puts in on almost everything.

Food pantries generally provide enough food to supplement three meals per day for three days. In one study (by Shackman et al, in the American Journal of Public Health, 2015; 105:e63-65), unemployment and food pantry use were significantly related (P ≤ .001). Ashley is a single mom, with a two year old and a four year old. Although New York City now offers pre-K to four year olds for free, free daycare for two year olds is hard to find and there is often a waiting list for Head Start vacancies. And as far as work goes – who offers free childcare for low-level jobs? It was a vicious circle with no respite in sight.

The NYC emergency food system includes over 1,200 food pantries and soup kitchens. They serve approximately 1.4 million people annually. Some of the pantries are large, serving hundreds of people each day they are open, and people can wait for hours on line. Some of these larger pantries offer ‘choice’ – a kind of grocery store style, where, depending on the size of your family, you are given a choice of a certain number of grains, proteins, fruits and vegetables. The majority of pantries are still small, using plastic bags filled with the same foods in each bag, distributed to their clients by a dedicated, voluntary staff.

The nearest pantry to Ashley is this smaller, and more typical one in the basement of the church. She leaves her two year old with her neighbor when it’s too cold and runs out to the church every Tuesday morning for a new supply. Her children like the cans of fruit, and Ashley has become very inventive with beans. When it’s warmer, she’ll take the two year old with her and wait on the longer lines at the bigger pantries, farther away. There she will have more choice, and more fresh items.

Spaghetti sauce is counted as a vegetable. Is it, she wonders? Well her kids like it, so she hopes it’s a vegetable. She has gotten a lot of spaghetti sauce lately, and puts in on almost everything.

Food pantries generally provide enough food to supplement three meals per day for three days. In one study (by Shackman et al, in the American Journal of Public Health, 2015; 105:e63-65), unemployment and food pantry use were significantly related (P ≤ .001). Ashley is a single mom, with a two year old and a four year old. Although New York City now offers pre-K to four year olds for free, free daycare for two year olds is hard to find and there is often a waiting list for Head Start vacancies. And as far as work goes – who offers free childcare for low-level jobs? It was a vicious circle with no respite in sight.

The NYC emergency food system includes over 1,200 food pantries and soup kitchens. They serve approximately 1.4 million people annually. Some of the pantries are large, serving hundreds of people each day they are open, and people can wait for hours on line. Some of these larger pantries offer ‘choice’ – a kind of grocery store style, where, depending on the size of your family, you are given a choice of a certain number of grains, proteins, fruits and vegetables. The majority of pantries are still small, using plastic bags filled with the same foods in each bag, distributed to their clients by a dedicated, voluntary staff.

The nearest pantry to Ashley is this smaller, and more typical one in the basement of the church. She leaves her two year old with her neighbor when it’s too cold and runs out to the church every Tuesday morning for a new supply. Her children like the cans of fruit, and Ashley has become very inventive with beans. When it’s warmer, she’ll take the two year old with her and wait on the longer lines at the bigger pantries, farther away. There she will have more choice, and more fresh items.